On the occasion of Jörg Kratz's second solo exhibition "Là où l'eau rêve" currently on view at the gallery, the artist and I discussed on his practice. Jörg Kratz has always created, drawn a lot as a child and been interested in the representation of trees. Although if the artist has started by depicting interiors that were always open to the outside world through the representation of windows, once his work shifted towards the direct representation of exteriors and vast spaces, the artist did not see this as a break but rather as a continuation. Indeed, he considers and approaches them in the same way. By choosing to depict them in small formats, he gives us access to these immense spaces as if we were observing them through a keyhole. Like the panoramas currently on display at the gallery, the elongated but very narrow formats only partially open up his landscapes, and visitors remain active in their observation, as if wearing binoculars. The idea of the movement of the gaze and the body involved in observing his paintings connects these two formats: approaching or looking at the works as sequences that are part of a single whole, like an unfolding frieze. Like his creations, which follow on from each other naturally, each time opening up an atmosphere, a moment, a particular element, allowing the creation of a unique work.

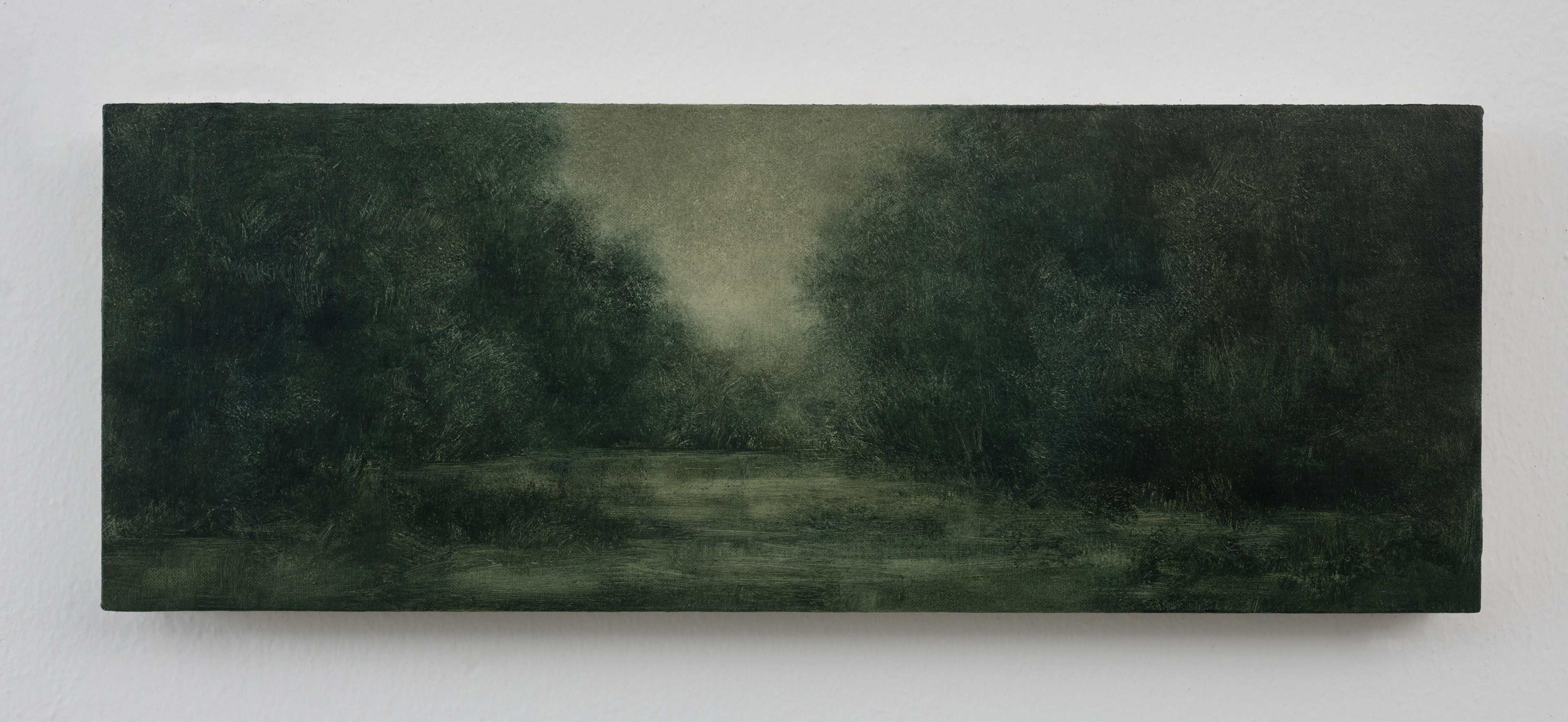

Jörg Kratz, crickets and mosquitoes, 2025, oil on canvas mounted on wood, 18 x 35 cm

"I suppose my work at its core is about memory and time, fleeting things. I am more interested in capturing the notion of a place, its atmosphere or an element of a place that resonates in our mind. (...) From thereon imagination takes over and people may connect with their own memories and connotations."

Jörg Kratz

Elsa Meunier : Can you introduce yourself? (Short bio, career path, what determined your choice to devote yourself to your artistic practice).

Jörg Kratz : I was a dreamy and playful child and always enjoyed sitting at my desk quietly, observing the trees in front of my window, drawing endless sheets of paper with figures, stories and imagined places or reading books. There was the urge to manifest what I had in mind in a physical form and this urge never left, rather became compelling. Having completed school I wanted to learn about the history and evolution of art which I studied then. Later I attended art school which is probably the place you go to when your imaginative thinking is directed inwards.

E.M. : When I first discovered your work, I was particularly impressed by the fact that you chose portrait formats to explore the landscape genre. Most of them are in 20 x 18 cm / 18 x 20 cm format, providing small windows onto what we imagine to be an immense landscape: that of the forest. What do you like about this format, and how did it become established in your practice?

J.K. : I always felt drawn to small format paintings as they require observation up close. You have to physically get really close to see everything and at the same time you are near to the materiality of the painting when the illusion of a painted space dissolves into pigments, texture and the tactility of the brushstrokes. For years I painted views of interior spaces and windows. There was a certain analogy between the format and the motif. As my work shifted towards depicting landscapes, trees and forests – which I still perceive as interiors – the formats became smaller, so there is a discrepancy between the vastness and depth of the motif and the actual physical size of its depiction. It might be like looking through a keyhole into an infinite space. The work is much more about the imagination of the viewers generating a scenic view of the landscape or the forest in their own minds.

E.M. : Recently you explore a new format: the panorama. What interested you in this elongated format ?

J.K. : When arranging paintings for an exhibition I think about the sequence and the visual narrative that unfolds between the works. This can be compared to a scenic experience, like that of a panorama which keeps our eyes in motion. I thought of the Bayeux Tapestry as well as of Japanese and Chinese scroll paintings that offer a visual journey through vast landscapes. Finding a composition or rather a rhythm – as there is less of a center – for these panoramas turned out to be a new challenge for me.

E.M. : I would like to talk about your titles. They seem to play an important role in your work. They suggest that, rather than faithfully representing nature that surrounded you, you seem more interested in paying attention to elements, sensations felt and experienced. The titles often evoke the sounds of the forest and its inhabitants. Like the small formats, which open like windows onto immensity, the short titles in turn open onto other worlds, poetic worlds. Can you tell us about the role of titles in your painting?

J.K. : Forests, in a sense, contain the memory of all living beings. They live slowly and perpetually upon the balance between decay and growth. I suppose my work at its core is about memory and time, fleeting things. As you state I am more interested in capturing the notion of a place, its atmosphere or an element of a place that resonates in our mind. This can be a scent or a sound or the humidity once perceived. From thereon imagination takes over and people may connect with their own memories and connotations. The titles I use are mostly drawn from Haiku poetry, often from modern Haiku by poets of the Beat generation, like Jack Kerouac. These are very playful and follow no strict rules and I combine them with the paintings intuitively. Sometimes they emphasize a sensation or oppose it or add some lightness or humor.

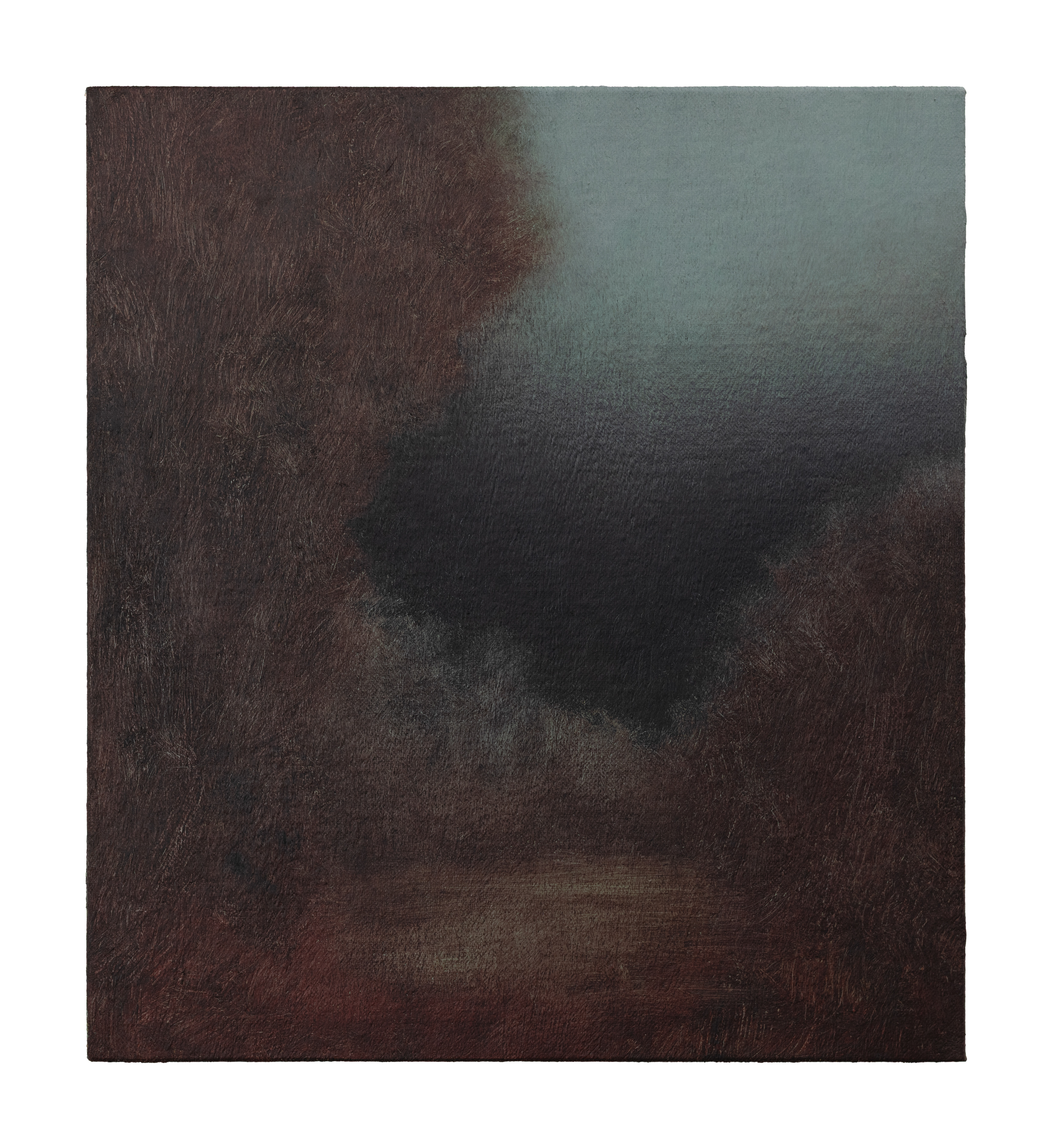

E.M. : Your landscape paintings often offer similar viewpoints, whether of the forest, trees or a pond, for example and without any inhabitants. But through your use of light, colour and brushstrokes, you highlight something very different in each one. A limited palette of motifs, but infinite possibilities. This is the theme highlighted in your current exhibition at the gallery: the motif of the pond punctuates each of your paintings on display. Could you explain what you want to highlight through each of your series?

J.K. : I do not really perceive my work as series. The process is quite open and unfolds organically. But there are recurring motifs and themes that accentuate, like the paintings of single trees or, for the current show, the pond. I noticed that water and its reflexions gained a growing presence in my work and I decided to do a group of paintings based on the motif of the pond. It is not an actual place and all the scenes are imagined – though it might loosely be connected to a place in the woods close to where I grew up. But it is based on my inner images and memories that I find hard to grasp as they keep shifting. So the paintings for the current show turned out to derive from a personal research on an imagined and probably rather dark place outside of time, marked by a particular melancholy or an unspecific longing.

Jörg Kratz, thunder in the mountains, 2025, oil on canvas mounted on wood, 20 x 18 cm

Jörg Kratz, walking over the water, 2025, oil on canvas mounted on wood, 20 x 18 cm

E.M. : Can you describe your usual artistic process for creating your paintings? Do you make sketches or preparatory works, or do you use mechanical image sources as support? (videos or photographies) or do you paint directly onto the canvas?

J.K. : I have no set process and although I try to work continually in the studio there are often long intervals between painting sessions which I devote to visual research, allowing myself to gather and assemble material and slowly forming new images in my mind. Then follow periods of intense work in the studio during which a larger group of paintings develops simultaneously. I mostly draw from imagination, sometimes I have an image in mind, at other times only colours I intend to utilize and the motif emerges from what I see in the applied paint. There are almost abstract pictures that give vague hints and mostly they reside in a state of spatial and atmospheric ambiguity. During walks in the forests near where I live I take pictures of organic forms, compositions and atmospheres that I might implement into paintings. Less often I use details of existing paintings from art history, such as Jacob van Ruisdael’s ‘Oak trees at a lake with water roses’ from 1665-70: I keep revisiting this painting and made several versions of the central scene with the trunks mirrored in the water, forming a cavernous enclosure.

E.M. : I would also like to talk about the support, you paint on canvas that are stretched on wood. Could you explain us this choice ?

J.K. : The decision for the support is practical. I paint on thin fabric that would dent under the pressure of the brush if stretched on a frame. Thus I mount the fabric on a wooden panel which resists the pressure of the brush or the cloth whenever I wipe off paint.

E.M. : What are your main artistic influences on your work in general? And which artist do you most enjoy looking now?

J.K. : There are many contemporary voices I admire – I wouldn’t know where to begin with. Dutch painters of the seventeenth century had a major influence on my work. Hercules Segers is a key figure among them. His dense painted prints of imagined mountains and valleys might not even have been intended for an audience and are probably the result of his experiments in the printing studio. In recent years I kept looking at painters Camille Corot, Édouard Vuillard and Tom Thomson and at how they transformed colour into notions of spatiality. Although I do not paint portraits, Giovanni Moroni is among my most beloved painters. His quiet elegance, his sense of serenity and depth bestows his portraits with a distinct humane touch. Film plays a role also, Aki Kaurismäki and Andrej Tarkovskij, especially ‘Stalker’ and ‘The Mirror’ as well as literature, Theodor Storm and his novel ‘Immensee’. In the past months I studied the drawings of trees by Albrecht Altdorfer, and the intimate sylvan scenes of Gillis van Coninxloo who was Segers’ teacher.

Jörg Kratz, hummingbird hums, 2025, oil on canvas mounted on wood, 18 x 20 cm

Jörg Kratz, the nightly moth, 2025, oil on canvas mounted on wood, 18 x 20 cm

Jörg Kratz, stars on the pond, 2025, oil on canvas mounted on wood, 18 x 35 cm

Jörg Kratz

Là où l'eau rêve

On view until Saturday January, 24th

Galerie Elsa Meunier

15, rue Guénégaud 75006 PARIS