Cette semaine nous partons pour les États-Unis et plus précisément à Louisville. Et c’est le peintre, galeriste, curator et poète, John Brooks qui nous ouvre les portes de son univers.

John Brooks a toujours dessiné depuis son plus jeune âge mais n’avait jamais vraiment envisagé de consacrer sa vie à sa pratique artistique. Il se vouait au domaine du sport et plus précisément au golf. C’est son déménagement il y a une quinzaine d’années à Londres et l’effervescence artistique de la ville qui a été une révélation pour l’artiste. Il décide alors de suivre des cours et de se dédier pleinement à la peinture, un médium qui le fascine depuis longtemps.

L’œil ouvert, l’artiste s’inspire constamment de ses contemporains et, féru d’histoire de l’art, regarde beaucoup les peintres du XXe siècle et plus particulièrement les expressionnistes allemands. La littérature mais aussi la politique nourrissent constamment le travail du peintre. Sa peinture mêle librement ces différentes inspirations et sa figuration fait dialoguer en une même composition des motifs issus de différentes époques et thèmes. À travers son travail John Brooks s’affranchit de toute contrainte réaliste et cherche à susciter des émotions fortes chez le regardeur.

C’est une conversation passionnante que je vous partage. Avec John Brooks nous avons échangé notamment sur son processus artistique, sa manière de composer ses œuvres et sur ce qui l’inspire.

John Brooks a toujours dessiné depuis son plus jeune âge mais n’avait jamais vraiment envisagé de consacrer sa vie à sa pratique artistique. Il se vouait au domaine du sport et plus précisément au golf. C’est son déménagement il y a une quinzaine d’années à Londres et l’effervescence artistique de la ville qui a été une révélation pour l’artiste. Il décide alors de suivre des cours et de se dédier pleinement à la peinture, un médium qui le fascine depuis longtemps.

L’œil ouvert, l’artiste s’inspire constamment de ses contemporains et, féru d’histoire de l’art, regarde beaucoup les peintres du XXe siècle et plus particulièrement les expressionnistes allemands. La littérature mais aussi la politique nourrissent constamment le travail du peintre. Sa peinture mêle librement ces différentes inspirations et sa figuration fait dialoguer en une même composition des motifs issus de différentes époques et thèmes. À travers son travail John Brooks s’affranchit de toute contrainte réaliste et cherche à susciter des émotions fortes chez le regardeur.

C’est une conversation passionnante que je vous partage. Avec John Brooks nous avons échangé notamment sur son processus artistique, sa manière de composer ses œuvres et sur ce qui l’inspire.

L'artiste John Brooks

" What I really am interested in is transmitting feelings, or what I call emotional resonance. "

John Brooks

Could you introduce yourself ?

I was born in Frankfort, Kentucky in 1978. From early childhood, I was fascinated with looking and making things—my parents say I was never without colored pencils or markers in hand— but art was not particularly accessible to me as a young person. It was treated more as a hobby than a calling. Though it is the state capital, my hometown is relatively small. There were no art museums and we didn’t visit them on our occasional journeys to larger cities; likewise, I didn’t know anyone who was an artist, so although I was passionate about drawing and painting, it was not something that felt particularly real to me. Nonetheless, I was encouraged to pursue my interests and my parents happily provided me with all the materials they could find or afford, and I even enrolled in a few special classes when I was young.

As remote a calling as being an artist seemed to be, there were threads that ran through both sides of my extended family. My mom’s family was and is keenly musical, so there was at least an appreciation for the arts. My dad’s family was more working class, which meant that artistic pursuits were even further out of reach, but my paternal grandfather, who worked as a foreman in the boiler room at a bourbon distillery, could draw beautifully and for many years had a side business painting signs, delivery trucks, and billboards by hand. Although it was firmly in the background, art did have a small presence in my life from the beginning.

My path to painting was long and circuitous. From around the age of ten, I became deeply involved in golf and for many years my life revolved around the game. I played in high school and for a couple of years at the College of Charleston in South Carolina. This is significant because although I wanted to study art in college, I also wanted to pursue professional golf. At the time, a career in art seemed even more remote of a possibility than a career in golf—I did have some significant skill—so I decided to study political science and English literature instead, with an idea that those fields provided more stability. I did take a few painting, drawing, and art history courses and loved them, but I still felt that art belonged to other people, not me.

After graduating in December 2000, I worked a few different jobs in the golf industry as well as in government / civil service while focusing on competitive golf. I never did turn professional, but I had some success at high levels of amateur golf, playing in three USGA championships and the prestigious Links Trophy at St. Andrews, Scotland. But by the mid-2000s, it was evident that I had reached the end of this path, and I was completely at a loss as to what to do with my life.

My partner Erik, whom I met in 2002, and I were living in Louisville, Kentucky, but starting in 2004, his work required him to travel to London frequently. Over the next year or so, his time there increased and I joined him for weeks at a time. In early 2006 we moved to London full time. This was the catalyst that changed my life and brought me back to art or to it fully for the first time; without London, I doubt I would be working as an artist. I had been adrift, but in London I found my way. From my very early days in the city, I started going to every museum and gallery that I could, devouring all of the incredible cultural riches that the city has to offer. I can’t necessarily recall why it started, other than just an excitement and great sense of gratitude that I had this new access to so much. I felt compelled to see as much as I could, and I became particularly enamored with painting—with its complexities, its peculiarities, its history, its mysteries. I wasn’t completely ignorant beforehand—I had interests and loves and favorites—but I was finally able to give in wholeheartedly to my curiosity.

I started painting and drawing again, and began taking continuing education classes at Central St. Martins, the Camden Arts Centre, and the Hampstead School of Art. I was also fortunate to travel a great deal, spending time in Paris, Berlin, Munich, Barcelona, Vienna, Venice, Athens, and other cities. So while I have had some training and education, I am largely self-taught and I have simply followed one interest or clue to the next, essentially creating my own curriculum.

We remained in London until the end of 2009, and then moved back to Louisville, then Chicago from 2011-2013, and have been based in Louisville for almost eight years. My practice did suffer at the time because of this peripatetic existence, but I am now grateful for the variety of experiences and the exposure to some of the world’s best museums and galleries.

In 2015, I took a painting course at AUTOCENTER in Berlin, studying under Norbert Bisky; and I have received three Artist Professional Development travel grants from the Kentucky-based Great Meadows Foundation, traveling to Berlin and New York City in 2019 and Miami in 2021.

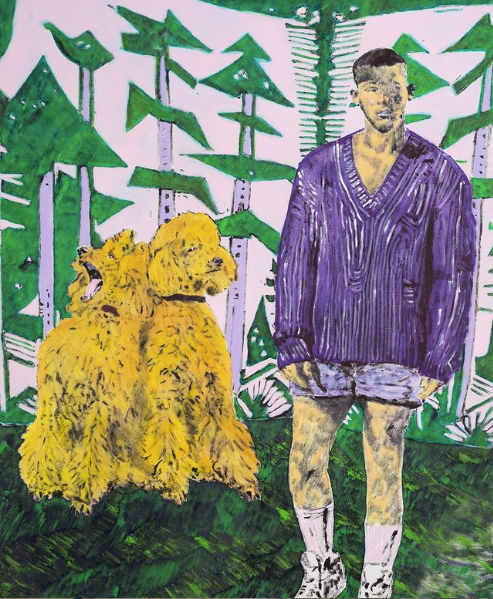

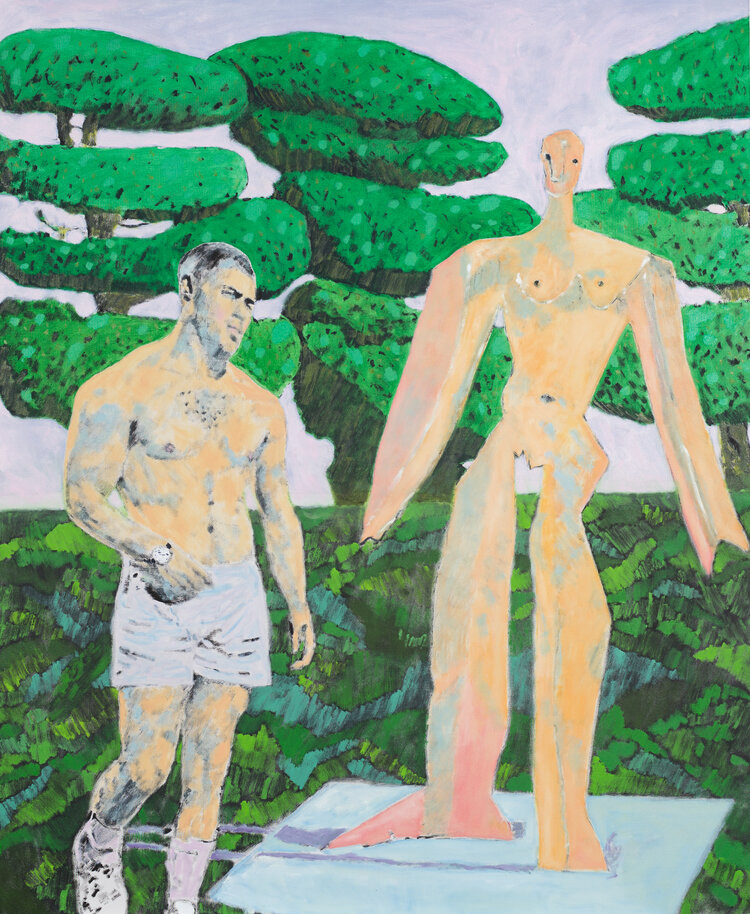

We All Come and Go Unknown / oil on canvas, 56 x 46 inches, 2021

In many of your compositions, you seem depict, in a same one, two different stories. In the scene the characters do not seem come from the same place or century. You accentuate the contrast by a play of scale between them. Could you describe it and explain the purpose ?

I have never particularly cared about technical precision or faithfulness to scale or perspective in my work. What I really am interested in is transmitting feelings, or what I call emotional resonance. This is how I respond, at least initially, to most work I see, hear, or read. Of course, I do care about color and concept and technique and a host of other things, but those concerns usually come after my emotional focus and response. For a long time, I tried to disregard or suppress this trait of mine, as if it was somehow illegitimate or a hindrance, but I have come to see it as an individual quality, as well as a voice to which I simply must listen. Every artist has a set of different strengths, and this connection to emotion is one of mine. It’s a kind of vibration to which I am attuned.

In 2018, after my practice felt like it was at a dead end or at least circling a cul-de-sac, my work underwent a huge aesthetic shift when I began integrating my painting, collage, and poetry practices. By using collage as a basis for composition, I transformed my work. In the beginning, there were (unshown) corresponding paper collages, as well as poems (also unshown) for each painting. Although I am no longer employing these paper collages or poems in this manner, the basic idea is still the genesis for how I conceive new paintings, and it is this origin that lends an air of dissonance to my compositions. I welcome it, and in fact seek it out. An image with a slight imbalance begs more looking, doesn’t it?

The various elements in my paintings are essentially nodes of connection: in “We All Come and Go Unknown,” for example, Nick Jonas and—returning to this idea of an unexpected use of scale—two large poodles, are paired with a background taken from a work by Karl Schmidt-Rotluff called “Russian Forest.” Each of these things hold meaning—multiple meanings—for me, and joining them creates even more complex and nuanced meaning, although it remains nebulous and not entirely graspable. Not everything I paint is borrowed or found, but many things are, and I like using these found things precisely because they arrive with their own weight and history, and I can add to or reshape those histories by using them however I want.

My interests in art history and politics seem to be converging. I have always been interested in art history—particularly the history of German art from the 10s, 20s, 30s, and 40s —and in this recent body of work purposely chose to bring attention to artists like Beckmann, Kirchner, Dietrich, and Sander because their respective histories and experiences have so much to teach us. Unbelievably, we seem to be headed down a dark road, repeating many of the mistakes (this word is pathetically small to describe these horrors) that caused so much suffering, destruction, and division in previous generations. Fear of the other will destroy us. But the past never leaves us; we carry it somehow, and it can serve us if we let it, but too few are willing to listen, at least for now.

I particularly notice that you often project on the skin of your characters or scenes a bright white light. It confers a dreamlike effect to your works. Is it what you are looking for ? Could you tell us a bit about your use of white in your paintings?

Painting is, to a large degree, concerned with light. I tend to use an expressive, severe light to signify emotion and experience. I work from photographs, and am drawn to the drama of light and shadow. For many years—really since I began painting again about fifteen years ago—I have, for a number of reasons, used both white and black extensively in my work. Firstly, I just like them! Part of the point of being an artist is to do what you like! I had two wonderful teachers—Roger Gill and Michael Major—at Central St Martins, and one forbade the usage of white but permitted the usage of black, and the other demanded the opposite. While I do understand the pitfalls of relying too heavily on these colors, they ARE colors, and I like using them as such. I also associate different colors with various artists—green and purple for Kirchner and Hockney; black for Beckmann; and white for Hodler, Doig, and Twombly. The list goes on. And, of course, I like the aesthetic result of using white light, as it does create a feeling of a figure in a space that hints at something real yet seems to exist in a realm just beyond the borders of reality.

In my previous body of work, made between 2018 to late 2019, there were vast areas of unpainted canvas with just the white primer visible. This was for two reasons: firstly, I simply liked the aesthetics of this method, but, more importantly, the “empty” spaces were meant to reflect the spareness of my poetry. As with my poetry and prose, I was interested in editing the work down to its most basic state. I may return to this at some point, but in my recent paintings I wanted to put more paint on the canvas.

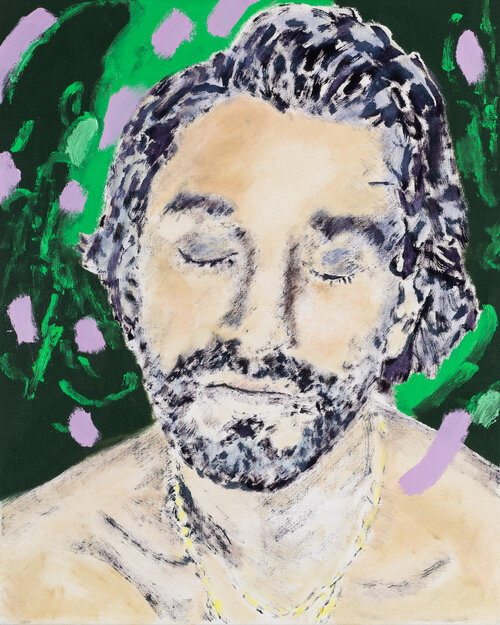

You and Me, We Got Our Own Sense of Time, 2021, oil on canvas, 16 x 20 inches

If sometimes we could recognize the settings, your backgrounds don’t always give us a lot of details of where the scenes took place and the perspective is freely created. You seem attached to decorative aspect and shape and also interested by the nature. Tell me about your search.

I am more interested in hinting at settings or locations or scenes than presenting them directly. In art, especially in painting, I find that the hint of something is often more compelling than an explicit explanation. I think of my compositions as containing scents of things; the scents are recognizable—or at least your senses give you the impression that you should recognize them —but they never quite materialize. That tension between the promise of an anticipated answer or resolution and one that never reveals itself is what keeps the viewer looking. It is what keeps me looking at works of art. Paintings aren’t math problems; there isn’t an answer. In a way, to understand is to move on, to forget, but the prospect of an answer keeps you engaged.

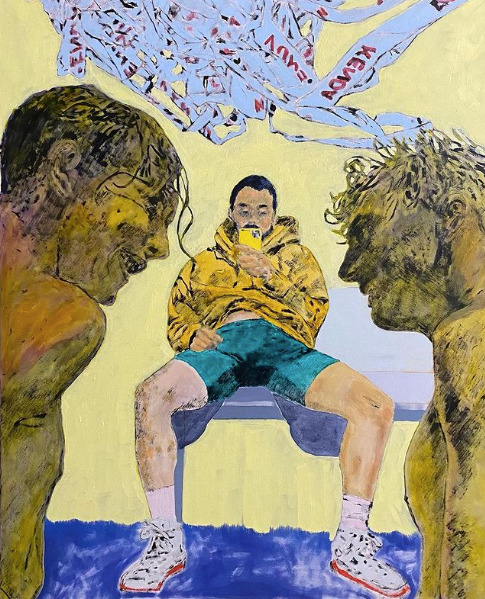

In this most recent body of work, in addition to using my own personal reference images, I have drawn heavily from art history, employing things that move me and hold significant meaning. I never want to copy, so I use my source material as a sort of architectural structure, almost like the support beams of a building, and then work freely from that. A great example of this is in the painting “Mind Over Matter is Magic;” the background is taken from a Kirchner painting, but unless someone was a Kirchner expert, it isn’t plainly evident because I have changed the colors so much and loosened up the pattern. Of course it matters greatly that it’s borrowed from Kirchner—these choices are never accidental nor arbitrary—but it isn’t so important for me to make that obvious. (There are other examples, such as the figures sourced from List and Sander, that are more obvious, but figures abide by a different set of rules in my work.)

I’m simply using source material that inspires me—because of shape or color or atmosphere. I have a cache of collected images and I am always looking for things that feel like they want to go together or speak to each other. The use of nature in this most recent body of work is fairly new. The natural world is hugely important to me—my poetry wouldn’t exist without it. I take great solace from long walks, hikes, and other such activities, but it hasn’t been present in my visual work too often. That is changing, and its inclusion has resulted in work that more fully reflects my whole self. The natural world, too, has an enormous presence in the history of art and painting, and I want to explore that.

In your work you seem to start to paint in black and then add the colors on it. Tell me about your creative process, how you go from blank canvas to finished painting?

I start every painting the same way, beginning with black to create the basic shapes and shadows of the figures and the other elements. Calling the beginning color ‘black’ isn’t fully accurate; I like mixing Williamsburg Cold Black with other colors—blues, burgundies, greens, occasionally purple. They’re quite subtle, so the color usually reads as black. I’m not quite sure when or why I started painting this way, but I’ve been doing it for a few years and it works for me. Years ago, I used thick graphite to create drawings on my paintings before I applied paint. I sort of think of this first step as a kind of drawing, almost like a preparatory cartoon one might make for a fresco. As of late, I haven’t been doing it that much on its own, but I do like drawing, and using the black with fairly dry brushes in this manner feels like drawing. It’s not exactly underpainting, as much of the black will be visible in the finished painting, but it is a kind of underpainting, I suppose. As they are the core of my work, I always begin with the figures and then add the background or other elements. In a way, I paint backwards, but I have a loose plan, so I know mostly where things are headed. Oil paint always has its own ideas— thankfully!—and there is a point where I let go of my plan and let the painting guide me. This is the most exciting and frightening part of the process, and it is why I keep painting. A plan is great, even perhaps necessary, but relenting to the desires and whims of the paint and the painting transports the work to unexpected places. It is in the obscuring, in the unknown, that each painting becomes itself.

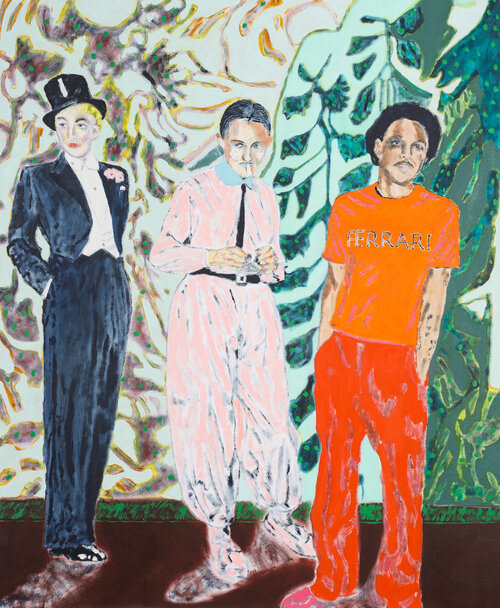

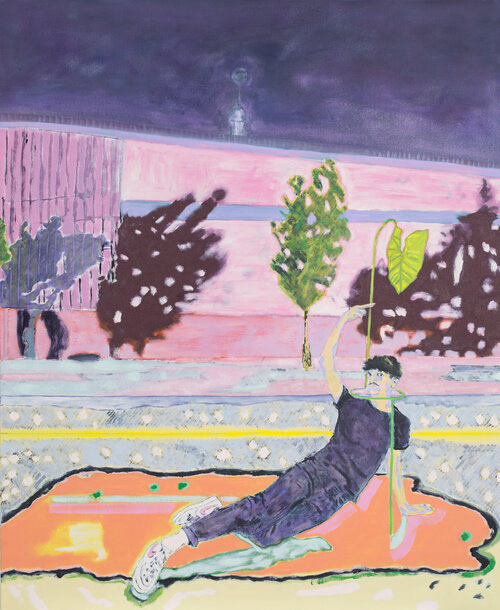

An Irrevocable Condition, 2021, oil on canvas, 56 x 46 inches

What are you working on at the moment?

My solo exhibition “We All Come and Go Unknown,” at Moremen Gallery in Louisville, just closed a couple of weeks ago. Crazily, most of the twenty-one paintings for that show were made in the two months prior to the show’s opening and I am still deeply intrigued by the techniques and concepts explored in the work, so I am following that path. Combining inspirations from art history with elements from literature, film, pop culture, the natural world, and my global community of artists, queer friends, and various muses seems, at the moment, to be inexhaustible. I have always had interest in a great many things, and with this new body of work, I feel, for the first time, like I am able to use my curiosity and knowledge to properly serve my practice. That isn’t to dismiss older work, but I feel like the work is becoming richer, deeper, and that feels like a good thing. Progress is always rewarding, and there will never stop being new things that oil paint—and oil paintings—can teach me. (Which reminds me, it has been a while since I have seen a Velázquez.) The more I paint, the more I fall in love with the medium, and I am just excited and happy to be able to spend time in the studio.

What are your main artistic inspirations ?

For the last fifteen years, the bulk of my time and life has revolved, one way or another, around art, and specifically painting. It is always painting. I’m grateful for the many opportunities I’ve had to see so much great work in some of the best museums, galleries, and collections in the world. If you’re really looking, the better you learn to see, and the better you know what you like—though surprises are always nice, too. I’m inspired by feeling, authenticity, color, strangeness, freedom. My creative energy comes from a place of longing, a place with a sense of something missing—what the Germans call Sehnsucht—and I am usually drawn to work that is somehow aligned with that feeling. What we don’t know is perhaps more interesting than what we do know, even if it makes us uncomfortable.

The German Expressionists were my first real love, and I’ll never stop looking to them for help. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, for whom my Standard Poodle Ludwig is named, Max Beckmann, Emil Nolde, Karl Schmidt-Rotluff, are always with me. The same is true for Edvard Munch, Henri Matisse, JMW Turner, Hans Memling, Ferdinand Hodler, Diego Velázquez, Francisco Zurbarán, R.B. Kitaj, David Hockney, Georg Baselitz, Cy Twombly, Barkley Hendricks, Norbert Bisky, Tal R, Noah Davis, Rainer Fetting, Peter Doig, Marlene Dumas, Markus Lüpertz, Luc Tuymans, Per Kirkeby, James Baldwin, Thomas Mann, Stefan Zweig, Robert Walser, Patti Smith, Michael Stipe, W.S. Merwin, Christopher Isherwood, Annie Lennox, Grace Jones, Marlene Dietrich, Lee Hazlewood, Willie Nelson, Emily Dickinson, Edward G. Robinson, Rostam Batmanglij, Frank Ocean, Leonard Cohen, Nina Simone, Marianne Faithfull, and Joni Mitchell, whom I think is without peer. I’m also very much interested in and inspired by artists such as Doron Langberg, Anthony Cudahy, Salman Toor, Louise Giovanelli, Gudmunder Thoroddsen, Meleko Mokgosi, Letitia Quesenberry, and Vian Sora, as well as contemporary queer writers like Garth Greenwell and Alexander Chee. This list could go on; there is inspiration everywhere, and I’m so grateful to so many artists and creatives.

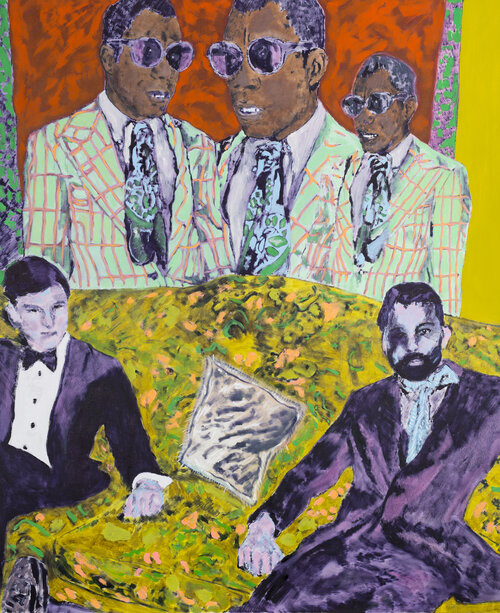

Mind Over Matter is Magic, 2021, oil on canvas, 56 x 46 inches

What haven’t we discussed that you’d like me to know about you or your work?

I should mention that I am also a curator and gallerist, having opened a gallery called Quappi Projects in 2017. Based in Louisville, Kentucky, the gallery just celebrated its fourth anniversary and we are preparing for our 23rd exhibition. I chose the name as an homage to the story of Quappi Beckmann and her husband Max, who, like so many others in the 1930s and 1940s, became refugees, battling nationalism, fascism, and fundamentalism. Sadly, given the state of politics in many places around the world—including my own country—their experiences seem highly relevant. The gallery focuses on showing work reflective of the zeitgeist; so far, we’ve exhibited work made by artists who live all over the United States, Germany, Brazil, Slovakia, and the United Kingdom.

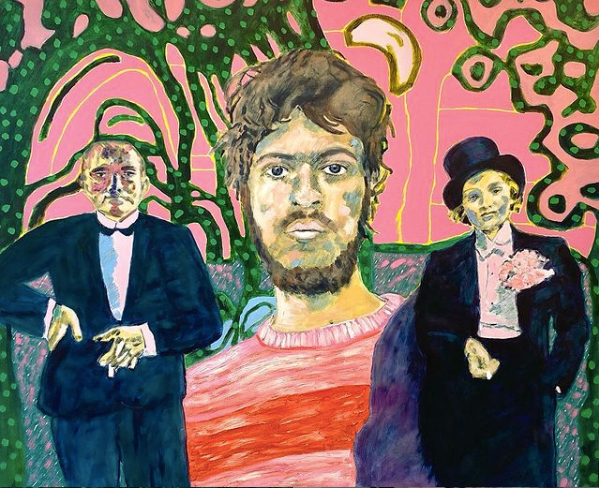

Help Me to Name It, 2021, oil on canvas, 56 x 46 inches

“Kentucky Reign” (72” x 60”)

T.O.Y.

A Bandit and a Heartbreaker / oil on canvas, 56 x 46 inches, 2021

“Cloudbusting”, 2021, oil on canvas , 46” x 52”

Degenerates, oil on canvas, 46 x 56 inches

Aschenbach and Wesley Crusher at the Lido

The Night of the Hunter, oil on canvas, 26 x 32 inches, 2021

Pour suivre toute l'actualité de John Brooks rendez-vous sur son site et sur son instagram: